Over the last few years, I have become increasingly concerned about how dysfunctional public discourse around divisive topics has become. This post is an attempt to collect my thoughts on some principles and strategies that can help push conversations in a productive direction.

The Problem

Throughout history, the topics of politics, religion, and even philosophy have brought about contentious disagreements, that’s nothing new. However, humanity seemed to be trending in a positive direction. It seems to me, that throughout most of our modern era, we had embraced the importance of rational discussion and free speech as a way to mitigate wars and violence, and saw it as an important mechanism of self-correction within institutions that foster it. Unfortunately, it seems that within the last few years we have begun to move further away from our ideal.

There are several reasons for this, most of which were unintentional, but I believe have caused a rise in tribalism and intolerance to opposing opinions. Social media has played a crucial role in this slide backward. Social media has been a revolutionary tool for communication, and connection, but I don’t believe we have learned the self-restraint necessary to use it properly.

Twitter, for instance, makes it so easy to find opinions that annoy us, with little context or nuance, and an audience to watch us embarrass our opponents. This is hardly the best environment to facilitate productive conversations about important and controversial issues. It plays right into our tribalistic behavior. In addition, the subconscious lack of empathy that comes from communicating through a computer or phone screen combined with online anonymity allows us to express ourselves in ways that would never be socially acceptable in person.

We also now have a 24-hour news cycle from a dying industry, which relies heavily on click-bait style headlines. When we consider even just these two factors we can begin to see how much of our information input perversely targets the worst parts of our humanity, and leads to dysfunctional discourse.

What We Can Do

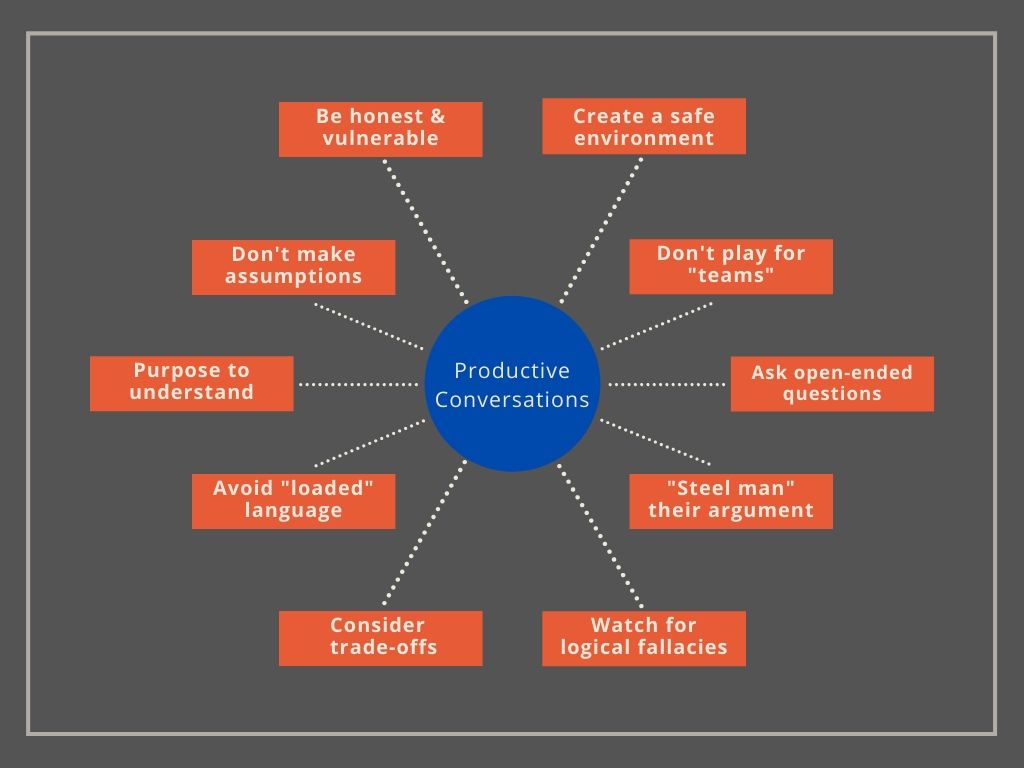

I certainly don’t claim to have all the answers and I’m not even sure what to do about the institutions that are no longer serving our best interests, but I have come up with 10 tips that we can implement in our own lives. I believe the more we all as individuals choose to model and advance healthy communication the more others will begin to embrace it as well.

1. Create a safe environment for conversation. If I want to have a real and meaningful conversation with someone then I want to try and connect with them on a deep level. In my opinion, this is how you get past the emotional, ideological, or unreasonable facade that many people put on. The people that are often hardest to communicate with may have a subconscious fear and are communicating out of self-preservation, not to find mutual understanding. If we do our best to reassure them that we are being fair and aren’t simply looking for a way to expose them, we have a much better chance at finding the reasonable and interesting human that is hiding in everyone.

2. Make your purpose understanding. We often go into conversations looking to change someone’s mind or at least show them how wrong they are. Yet how often does that actually work? When we go into a conversation with the intent to change someone’s mind we often lose any opportunity to do that. Instead, if we come with the intention to understand, we open ourselves up to real dialogue. A process which, finds common ground, is curious about differences, and may actually give both parties a more nuanced perspective by the end of it.

3. Don’t make assumptions. It’s easy to assume you know what another person believes based on what they’ve said before, how they act, etc. However you likely only have a piece to the puzzle, at best. Opinions change, sometimes people say things they don’t mean, so it’s almost always better to clarify rather than assume. After all, we should be trying to understand one another.

4. Don’t play for teams. This should be obvious at this point, but I believe it’s a bad idea to think of yourself or the person you’re talking to in terms of group affiliation. Very few people in my experience check off all the boxes for whatever group they may choose to associate with, and it is often where and why they diverge that give us the most insight. Not only does playing for a team start you out with a competitive framing, but it is also inviting you and your partner in conversation to make assumptions.

5. Avoid loaded language. Using language that is disparaging, accusatory, opinionated, or overly emotional will usually detract from the conversation. Of course, in some instances, it is necessary or useful to discuss how something makes you feel, but when it comes to discussing ideas it typically comes across as trying to subtly influence the conversation in one party’s favor.

6. Be honest and vulnerable. Freely admit when you don’t know something, or when you’re wrong. One of the fastest ways to lose respect in a conversation is to be proven wrong about something and not take ownership and correct it. You immediately identify yourself as an unreasonable person. When you are honest and vulnerable it usually lets the other side feel free to be vulnerable as well. This improves the chance of real connection and real understanding.

7. Ask open-ended questions. Using questions can avoid defensiveness and also improves your ability to understand their perspective. By giving them a chance to fully explain their position, and listening you can begin to accurately understand not only what they believe, but why. This often helps steer the conversation in a way that you can actually grapple with the core disagreements you may have. Consider questions like; What has led you to believe this? Have you considered logical consequence x? What sort of evidence would change your mind? Not only are these good questions to ask other people about what they think, but they are also questions you should ask yourself about your own positions.

8. “Steel man” their argument. Most of us are familiar with a “straw man” argument, where one person will intentionally misrepresent someone else’s argument so that it is easier to defeat. To “steel man” an argument is to do the opposite. You intentionally discuss the best-case scenario or the strongest version of the other person’s argument. Almost any position a person will take has at least a grain of truth or some merit to it, so it’s important to give credit where credit is due. In addition, it stays in the spirit of productive conversation and genuinely trying to understand who you’re talking to. Another way I like to think about this is to never attribute to someone a position they would not take on willingly. Only attack positions that the person will “own” as theirs, otherwise you may waste your time defeating an argument they don’t agree with. A great way to work through this is to try and paraphrase the other person’s point in a way they agree with, to make sure you fully understand what they are saying.

9. Consider trade-offs. Every idea or solution is going to have trade-offs and sacrifices involved. When discussing your own views or someone else’s, consider what would have to be given up to achieve this, and what the long term consequences would be. This is often a great place to find common ground. If both sides can admit the flaws or negative aspects of their own perspective, they can begin discussing what lines should be drawn and what sacrifices are worth making. While they may not come to the same conclusion, this type of awareness can often lead to better understanding and more respect for the other person’s position.

10. Learn about common logical fallacies. Part of having productive discussions is recognizing flawed logic in either party’s position. Learning about the most common logical fallacies, at a minimum, is a good step in presenting sound arguments and refuting fallacious ones. I think it’s also important to point out that using a fallacy doesn’t automatically mean that the point is wrong, rather it is pointing out that it doesn’t logically follow. For example, if someone says that x is the best medicine because a doctor said it was. This is an appeal to authority, however, the research and medical training that the doctor went through may very well point to x being the best medicine, but it isn’t automatically true simply because a doctor said so.

There are many resources online for learning about logical fallacies. Here is a good resource for getting started. https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/academic_writing/logic_in_argumentative_writing/fallacies.html#:~:text=Fallacies%20are%20common%20errors%20in,evidence%20that%20supports%20their%20claim.

Conclusion

While we cannot control the news, social media, or the people we disagree with, we can still control ourselves. If we take the time and effort to try and understand those who have different opinions than our own, we may find that people are often more reasonable than we give them credit for. We may also learn that we are actually allies in the fights that matter most, even if we differ on what the most effective approach is. This may not be as immediately satisfying to our ego, but it has many advantages and fewer pitfalls than simply proving how right we are to other people.

He who knows only his own side of the case knows little of that. His reasons may be good, and no one may have been able to refute them. But if he is equally unable to refute the reasons on the opposite side, if he does not so much as know what they are, he has no ground for preferring either option.

– John Stuart Mill